Recently, I had a series of epiphanies about my experiences as a founder. Please forgive the length of the post, and stick with me, I’ll do my best to make the journey worthwhile.

I was eleven years old, maybe twelve, and my family lived way out in the middle of nowhere, in unincorporated King County. We were a 15 minute drive (at 45mph) to the nearest grocery store. My geographically closest friend’s house was another 20 minute drive from there. Walking to anything besides the frog pond in the giant forest behind our house would have taken hours. I never attempted it.

10 (maybe 11)-year-old Rand posing for a school picture

I played with the neighbor kids sometimes, but even then was an introvert. I liked video games, looking for frogs in the forest pond behind our house, re-watching the same handful of movies again and again, and my Transformers, Care Bears, and G.I. Joe’s (I had elaborate backstories involving all of these assorted characters, which is how Optimus Prime and ShareBear fell in love).

That year, our next door neighbors moved, and my parents bought the house for a song, then rented it out. But, before they did, we took a look through all the stuff left in the house. Most of it was in the garage, and most was junk. But, I can still vividly recall a bright red plastic briefcase with two snap closures that caught my tween eye. When I opened it, I found the case filled with old baseball cards. Most were from the ’70’s and ’80’s, but a few were from earlier eras – the ’60’s and even ’50’s.

The Internet was still years away, but my mom promised that I could walk to the baseball card shop near her office the following week after school (I spent most after-school afternoons at my mom’s various office spaces, waiting until she was done for the day, often watching my little sister and/or brother). She gave me a little bit of cash and said I should buy a guide to Baseball card prices. The shop had one called “Beckett” (and, impressively, it looks like they successfully transformed into an online guide sometime in the last 20 years), which I acquired, took home, and researched like a hawk.

I discovered that some of my cards were worth a great deal — $80, I think, was my most valuable baseball card. A few months later, after obsessing over baseball card prices and options, I sold almost the entire collection (with a few exceptions I’d come to cherish — including a horribly beat up Mickey Mantle card that I couldn’t bear to part with) to a collector at another shop I’d found by pouring through taped-up notices in the back of the stores. I made, all told, somewhere around $350. To a twelve year old in 1991, it was a fortune.

I had a best friend with whom I shared my windfall. We plotted and schemed for months about what to do with the money, eventually settling on mostly video games, with enough set aside to buy some candy twice a week from the 7-11 when I’d go over to his house. I remember being so incredibly jealous of the small apartment he shared with his mother and grandfather, because he could walk to a bookstore, a 7-11, a movie theater, and loads of other shops and restaurants. I swore that when I grew up, I’d live like him, though on reflection, the two bedroom apartment he and his family shared was probably quite rough on his mother and grandfather.

But, like most kids, I couldn’t resist the burning urge to spend my newfound cash, and eventually, my many trips to the bookstore resulted in a purchase — the Dungeons and Dragons “Rules Cyclopedia,” published that same year.

The book my 12-year-old self couldn’t put down

I had read every page of that book three times before buying it. I’d walk to Barnes and Noble from my mom’s office, to a section of the store I could probably walk right to today (if the building still exists), read for 45 minutes, then walk back to my her office in time for the long drive home.

But, even then, I knew not to share it with anyone, even my best friend. D&D was, I’d learned from schoolmates who mocked it, for only the dorkiest, nerdiest, most lonely, pathetic kids. I kept my obsession secret. I didn’t tell anyone. That next summer, I tried to get my parents and grandparents to play with me, but they weren’t interested (at least they didn’t shame me for it, though I could tell my attempts made them uncomfortable). I tried getting my sister, Meridith, to play, but she was only seven, and the game was a combination of too complex and too scary.

So, one day, at thirteen, I worked up the courage to ask three of my friends if they’d play with me. I understood from hundreds of readings of the book that three players and one narrator/storyteller (that the book called “The Dungeon Master”) was an ideal combination. I was so scared of rejection, and had built up the moment of denial so much that when it came, I felt something almost akin to relief.

“OK,” thought early-teens, acne-riddled Rand, “We knew this would happen. Play it cool.”

But that experience sucked worse than I’d anticipated. My “friends” in this instance weren’t close friends — I had too much at stake to risk asking them. But they were gossipy friends. They told other people at my school, who told others, and I went from being a shrimpy, bad-at-sports, kid to a full-blown, untouchable level of nerd. It was such an overwhelmingly awful and inter-personally clarifying moment for me that for decades, I’ve repressed the memory, and with it, my obsession was that book.

The book itself became waterlogged — I think I took it on a family trip and dropped it in a pool. I remember trying to make hand-drawn and hand-written copies of the pages that stuck together and bled, but can’t recall whatever happened to the tome. By high school, it was long forgotten, but the lesson stuck with me: NEVER talk about D&D. NEVER ask anyone to play with you. If you do, you’ll be a friendless outcast.

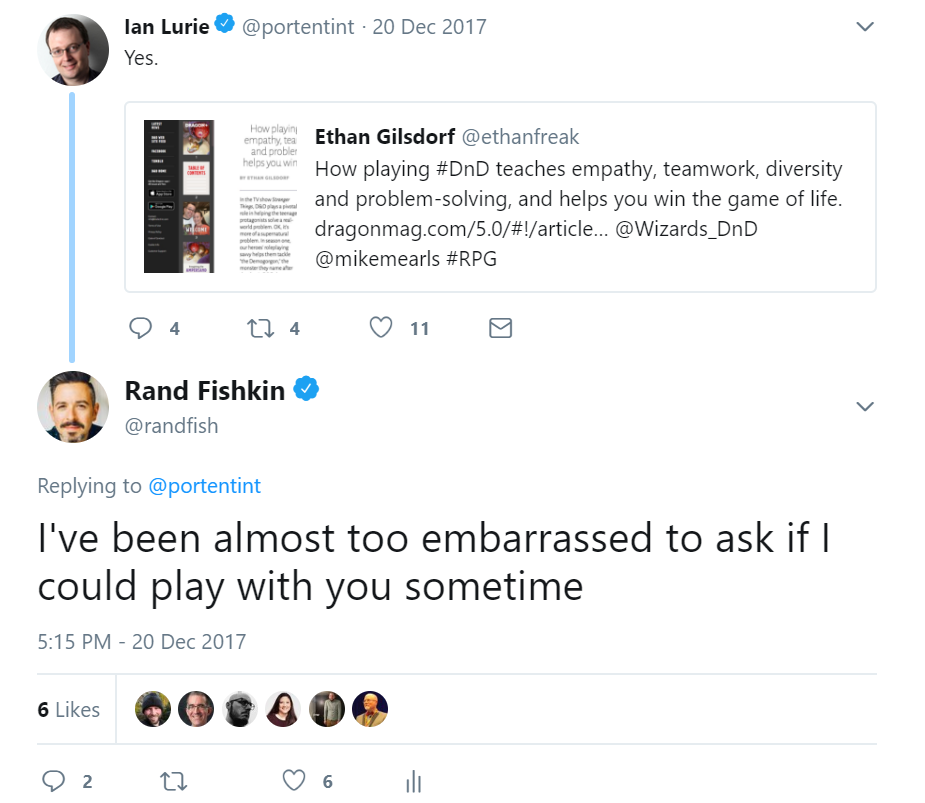

It wasn’t until a quarter century later — yes, 25 full years — that this happened:

Ian Lurie, who’s been a leader in the SEO and web marketing field for years, is unabashed about his love for the game of D&D. I’ve watched him give marketing presentations themed with D&D lore and insider jokes, always pretending that I didn’t get the humor because the residue of that teenage ostracism still clung to me.

But Ian was as good as his word on Twitter. And a couple months ago, this happened:

Left to Right: Andrew Bohrer, Tony Wright, me, Geraldine, Ian Lurie, and Dawn Dort

Left to Right: Andrew Bohrer, Tony Wright, me, Geraldine, Ian Lurie, and Dawn Dort

(photo credit: Michelle Broderick, who stood on a chair to get us all in)

Ian ran a game for me. He brought his wife Dawn, whom Geraldine and I have grown very attached to over many years of dinners in various cities around the world. I invited some friends I knew who played. And…

We got to kill monsters and find treasure and solve puzzles and talk to people who needed our help and buy things that would help us kill monsters better. It was everything I’d always wanted. I was so excited in the days leading up to it that I could hardly sleep. I was so excited after it that I instantly bought five more D&D books, started following the various D&D subreddits, and got… obsessed. The way only a 38-year old who, through shame and fear, spent 25 years hiding something he loved away from the world.

This is how deep my shame runs… I didn’t tell Geraldine, not in all the seven years we dated, or in the last 9 years of our marriage, that secretly, desperately, I wanted to play D&D.

My fear of being labeled, of being excluded, of being judged cost me decades of fun, of friendship, of shared experiences. That’s what shame does. What peer pressure does. They cut away parts of our lives and leverage fear that keeps us from being who we want to be or doing what we want to do.

When I started sharing this experience, tepidly, with a few friends, I found out how incredibly not alone I was. I cannot count the number of people I’ve told who’ve said to me, “Oh yeah, I play with my kids,” or “Oh yeah, I’m part of a group; do you want to join?” All this time I’ve been hiding, they’ve been playing. But it took Ian’s openness — his unabashed, unafraid, come-at-me-with-your-judgement attitude — to open those floodgates of acceptance.

And, D&D led me to this (start at 0:40, and go to 1:31 – that’s the bit I want to talk about):

It’s a video from a guy named Matthew Colville, who gives advice on running games. I’ve transcribed what I heard as he spoke:

“I think one of the biggest mistakes people make is to assume that any group of employees could all have fun building a company together if only you were good enough CEO. If only I paid more attention to what my employees like… If I only had more time to prepare the stuff they like… No it’s actually very hard to grab a group of people and make a band out of them.

There are very few bands like Rush, where they all get along for forty years. Most bands are like The Police and they hate each other. You get a few good albums out of them and you count yourself lucky that it lasted that long.

So when you get your band together for the first time, absolutely be critical of your own work. As founder and CEO, you will spend the rest of your life getting better. Absolutely pay attention to your employees and try to learn what they like so you can put the content in front of them that engages them.

But… be open to the possibility that it was not meant to be, and that this is not a failing on your part. Sometimes the book you want to write is not the one they want to read. That doesn’t mean it’s a bad book or that they’re bad readers.”

I think I cried when I heard Matt say “this is not a failing on your part.” I no longer heard him talking about D&D. I heard him talking about Moz. I heard him forgiving me for all the mistakes I made, and all the people I feel I’ve let down. Somehow, suddenly, a guy giving advice on how to play a super-nerdy tabletop game on a YouTube channel brought my entire professional life into relief.

It’s beautiful. It’s life-affirming. It’s so damn freeing to think that what we build might just be good enough, and that if it doesn’t work out for everyone, or if everyone you bring to your game or your company isn’t happy or productive or having a good experience, that is OK. It’s not your fault. And it’s not their fault. Sometimes, the company you create isn’t the one they want to build.

Maybe, as you read this, you think it’s a shallow insight. But I promise that everyone who’s ever created something for others (a company, a product, a story, a song, a piece of art, or, yeah, a game where people pretend to cast spells and fight monsters) knows the feeling of guilt, of failure when what you’ve made didn’t resonate. When that happens, we only have two parties to “blame,” the creator and those experiencing the creation. But this binary, like so many, is broken. It’s bullshit.

“Be open to the possibility…” that’s what Matt said. And with that openness comes forgiveness, and the freedom to go out and try and fail again and have that be OK too.

I have two hopes for everyone who creates:

- That whatever it is you feel shameful about, whatever it is you feel the need to hide, so long as it’s not a hateful view or malicious intention, you free yourself from that shame. I’ve been utterly amazed by the support my friends have shown me, and you might be, too.

- That you be open to the possibility that what you’ve created and what you will create doesn’t need to resonate with everyone. That the company you build may have ex-employees who say “I hated that place! They suck!” and that’s OK, and it might not be your fault, and it might not be theirs.

These past few weeks, D&D has become a big part of my social life. I prepare for games, I read about it, I nerd out on Reddit, I anxiously await Ian’s next adventure, I’m even learning to be the storyteller myself for another group of friends. Geraldine has jumped in, too. She has different goals in the games, but I love it:

Him: Please stop trying to seduce the Paladin. He’s celibate.

Me: What I’m hearing is that I have to roll with disadvantage.#outofcontextdnd

— Geraldine (@everywhereist) May 25, 2018

I feel like we’ve found this whole new world to explore together, and my only regret is that I couldn’t be transparent about it until now.